In the crowded slums of Lagos, Nigeria, untreated sewage mingles with the chaotic network of pipes that deliver water to the city. Those who can't afford a local borehole or a private vendor know better than to take their chances with the taps -- most preferring to go thirsty instead.

That's according to Olatunbosun Obayomi, a Lagosian microbiologist and inventor who has lived in the city all his life.

But now Obayomi thinks he's found a solution -- one that not only tackles the slums' sanitation issues, but creates free, clean energy in the process.

"With a cheap retrofit, household septic tanks -- the source of the sewage -- can be converted into biogas generators," said Obayomi, 29, whose concept has earned him a TED fellowship, a Nigerian Youth Leadership Award and growing international acclaim.

"The idea of turning waste into energy has been around for centuries. My innovation is simply applying the chemistry in a practical way by using the resources we already have," he explained.

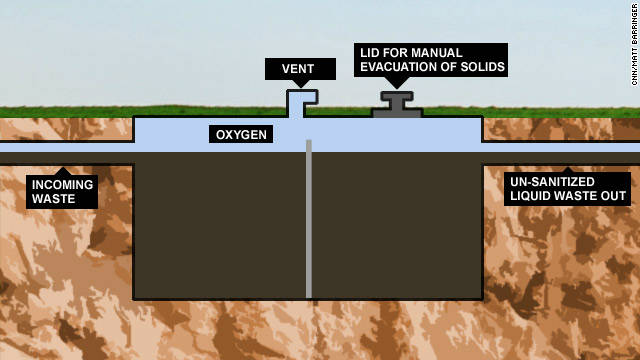

In most homes in Lagos, toilet waste is stored in rudimentary septic tanks beneath the ground. Here it decomposes into a poisonous compound, before being sucked out by a tanker that deposits it all in a nearby lagoon.

"Unfortunately, the system of water pipes is very disorganized, and they often pass through the same place where the sewage is dumped," said Obayomi. "And it's not uncommon for poorly constructed septic tanks to leak directly into the drainage system."

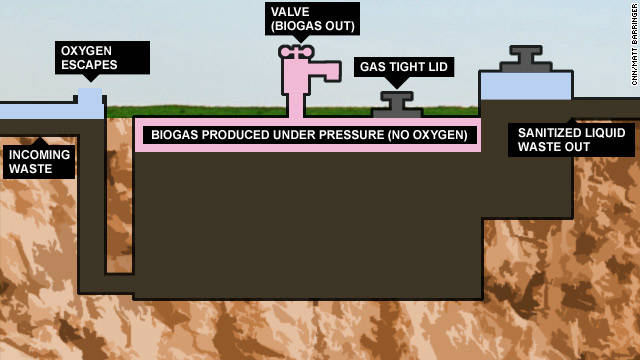

But rather than attempt a wholesale overhaul of Nigeria's waste system, Obayomi's approach makes use of the existing septic tanks -- equipping them with new waste entry pipes that remove oxygen from the decaying process.

But rather than attempt a wholesale overhaul of Nigeria's waste system, Obayomi's approach makes use of the existing septic tanks -- equipping them with new waste entry pipes that remove oxygen from the decaying process.

As he explained: "When excreta decompose with oxygen, it creates a useless, incombustible mixture that carries disease. But without oxygen, the germs die and the mixture produces a combustible gas."

This biogas -- a mix of carbon dioxide and methane -- can be stored in an adjacent underground chamber and used to power cooking stoves, heat homes or even generate electricity.

"Converting waste into biogas is a win-win strategy," said Sarah Butler-Sloss, founding director of the Ashden Awards, an organization that champions local energy innovations around the world.

"What makes it so elegant is that it resolves a life-threatening sanitation issue -- by treating harmful, waterborne germs -- while simultaneously creating a much-needed source of carbon-free energy," she said.

Butler-Sloss added that recent figures from the U.N. say 1.4 billion people worldwide have no access to electricity, while 2.7 billion still prepare food on grossly inefficient and carbon-hungry open fires.

"We have seen similar projects in places like India and China -- where everything from domestic garbage to animal waste has been used to produce energy with great success ... Clearly this is the time to embrace domestically produced biogas, especially in the developing world."

It's a view shared by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

Patrick Mwefigye is program officer for sustainable consumption and production at UNEP's regional office for Africa. He says that in areas where there is "little funding, capacity or infrastructure" for complex waste management, "we see the production of biogas as having great potential."

At present, Mwefigye says the gas is regularly produced in just a handful of African nations.

"In Rwanda, for instance, the prisons have been fitted with large biogas generators, so that they are almost entirely self-powering," he said.

But, although Obayomi's retrofitted biogas generator is relatively cheap to build -- requiring only low-tech materials such as plastic pipes, cement and sand -- and despite all the recognition it's attracted, only a prototype has been installed so far.

Yet Obayomi conservatively estimates that the average street in Lagos could produce 1,720 liters of biogas a day -- enough for an engine-powered water pump to serve the daily domestic needs of at least 50 families.

So what's the hold-up?

"Biogas generators tend to be constructed in situ," said Butler-Sloss, "And while the materials are relatively cheap, they're not mass-produced like solar panels or wind-turbines so, at present, it's difficult to scale-up."

Obayomi has a different take, however. For him, it's not an issue of resources or need, but attitude.

"Although I've been filmed by government TV and won these awards, no politician has approached me to build anything. In Nigeria there is a lot of talk but very little walk," he lamented.

There is also a problem of credibility, he said. In Obayomi's experience, the hardest place to be taken seriously as a Nigerian inventor is in Nigeria itself.

"It is a new concept for many Nigerians," he said. "There's still this feeling that unless an idea or a piece of new technology comes from the West, then it's not glamorous ... it's not valid."

No comments :

Post a Comment